GitLab's Semi-Linear Git History

Photo by Yancy Min on Unsplash

Photo by Yancy Min on Unsplash

Introduction

Working with multiple developers on the same project can often result in messy git histories and unnecessary merge commits when updating feature branches from main.

Moreover, merge requests might not be based on the latest version of main when all CI checks pass and manual testing is done. This can result in CI passing on the merge request but failing once merged to main. Or even features that were working when tested on the feature branch, that broke after being merged to main.

Lastly, a non-linear history results in commits from a feature branch being scattered on the main branch, ordered only by the commit’s timestamp. This can make it hard to trace which commits were introduced in which order and makes it virtually impossible to check out previous commits without including various other unrelated changes.

In this post, we will take a look at some of the different merge strategies and how GitLab’s semi-linear history can help you keep a much cleaner git history.

A non-linear history

If a merge request MR#1 is based on an older version of main, the tests that run on the merge request are not guaranteed to pass after being merged to main. This is because newer commits on main could conflict with or break code on MR#1 without necessarily having a merge conflict that prevents MR#1 from being merged.

Naturally, this could be solved by always merging main into a feature branch before creating a merge request. However, there are a few drawbacks to this merging strategy:

-

It requires the developer to manually update their branch from main locally before creating a merge request. This can be forgotten or done incorrectly.

-

It puts the responsibility of the branch being up to date on the developer, without an easy way to see this on a merge request.

-

It creates superfluous merge commits like Merge branch ‘main’ into ‘feature-1’

-

Commits from different branches get entangled quickly because they are kept in order of time. This is easiest to explain visually. So I will demonstrate this below.

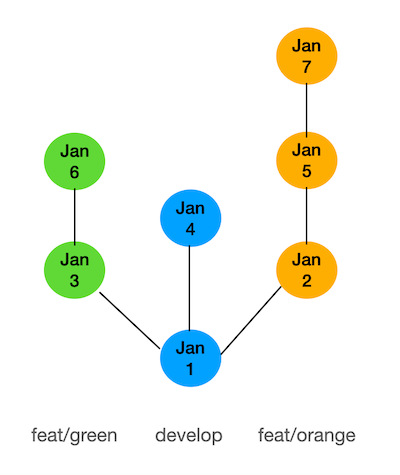

Let’s look at a straightforward git flow. Commits in blue are (merge) commits on main. The green and orange branches have the same root on main and are developed in parallel (simulating two developers working on different feature branches simultaneously). Furthermore, there is an extra commit on main (simulating a hotfix, a third branch being merged or something along those lines).

The merge request for feat/green is merged on Jan 7 and feat/orange is merged on Jan 10. Before merging the feature branches were first updated from main which is necessary to ensure the CI on the merge request includes the latest commits on main.

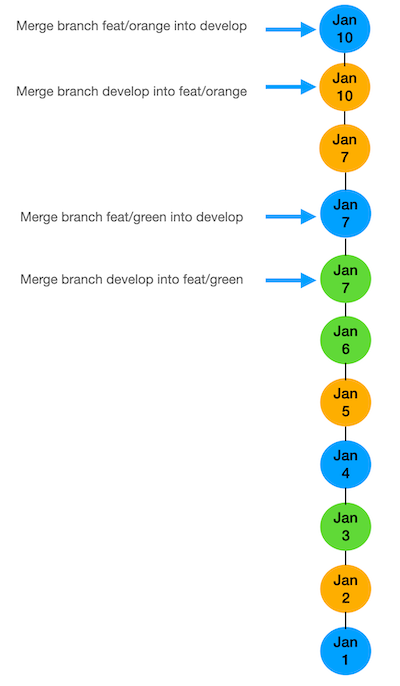

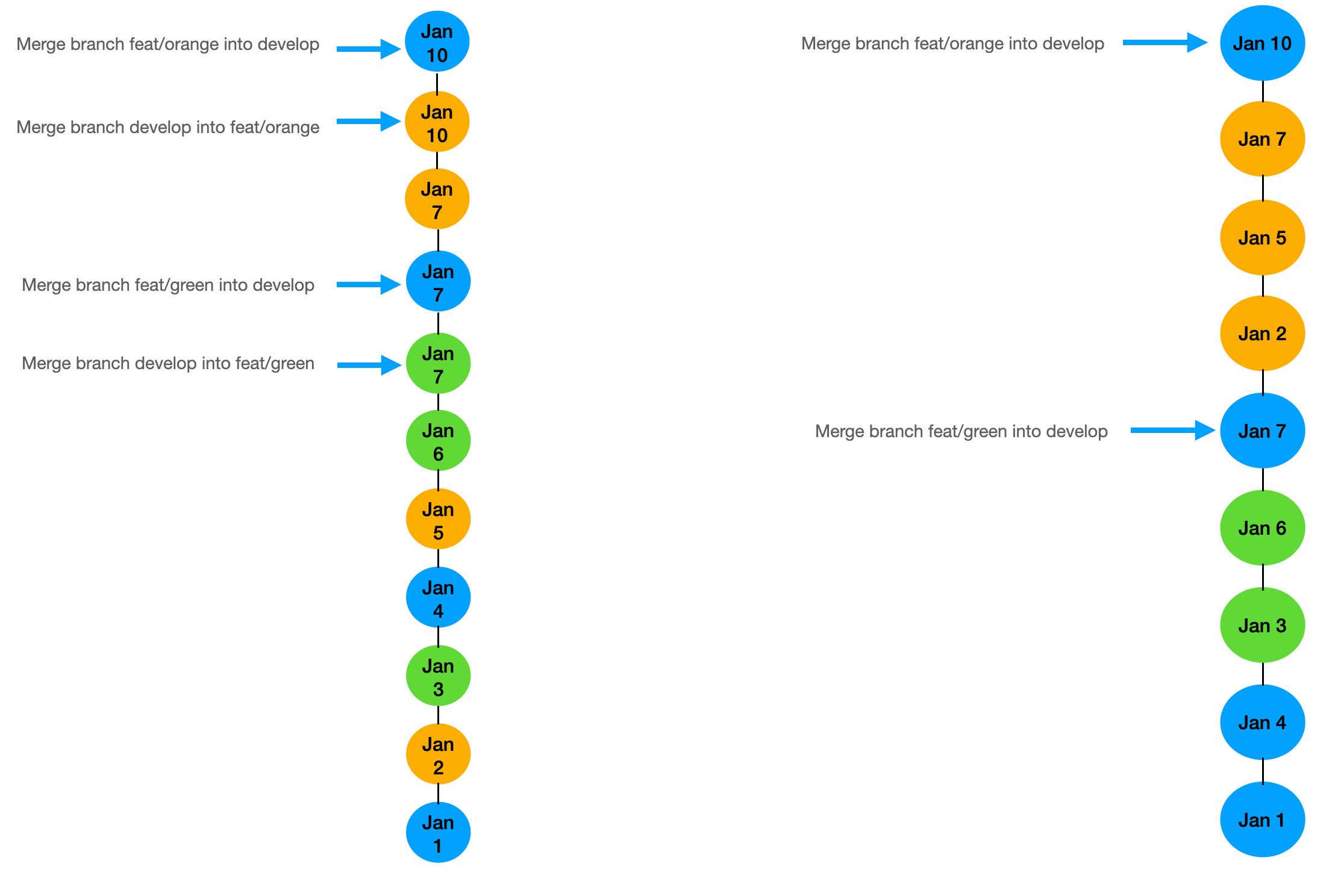

With a standard non-linear history where branches are updated from main using git merge we would get something like this:

The three main issues are that we have lost a bit of traceability on which commits belong together, it would be a lot harder to check out an earlier commit without also throwing out any commits that happened after that on different branches and lastly, we have created two unnecessary merge commits when updating our feature branches from main.

This can quite clearly make the git history difficult to read and manage without visual editors that draw all the diverging branches for you like GitKraken. Whilst being able to see the diverging branches on an editor can come in handy, it can also get hard to read very quickly if you don’t keep a clean git history.

A messy Git history. Source: When do you use Git rebase instead of Git merge?

A messy Git history. Source: When do you use Git rebase instead of Git merge?

One important thing to note is that these problems get considerably amplified when you increase the number of developers working on a repository or the time spent on a feature branch (or both).

A linear history (fast-forward-merge)

I’m going to skim over this one rather quickly as I truly believe this is never the right way to go for any project that has more than one developer.

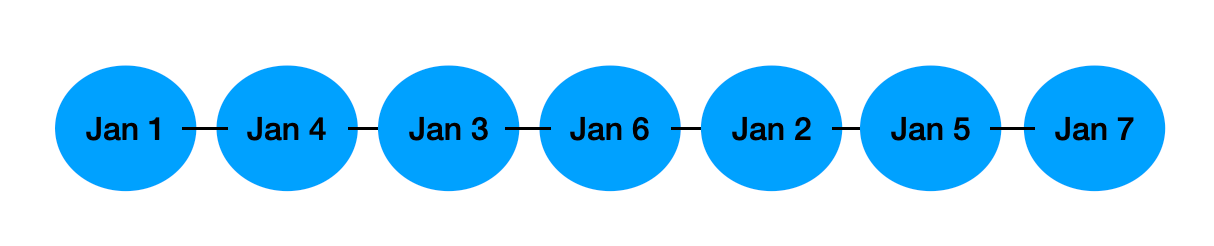

A fully linear history is a history in which all commits are added on top of each other in a straight line. This can be achieved by keeping feature branches up to date with main using git rebase and then merging the feature branch into main using git merge --ff-only. This will result in a fast-forward merge where the commits from the feature branch are added on top of the latest commit on main.

GitLab has the option to enforce this, but I would advise against it. If you use this merge method, there will no longer be any merge commits on your main branch. This means you will no longer be able to revert all the commits from a single merge request in one action. Besides that, you won’t be able to see any distinction between commits from different merge requests, unless you go onto the actual merge request on GitLab. If we go back to the example used above we would simply end up with a straight line with no merge commits and no way to tell which commits belong together (even in visual editors like GitKraken).

A full linear git history, otherwise known as “Traceability Nightmare”

A full linear git history, otherwise known as “Traceability Nightmare”

A semi-linear history

To solve some of the issues from both strategies mentioned above, we can use GitLab’s semi-linear history. By adopting a semi-linear merging history we take the main advantage from a non-linear strategy (merge commits) and combine it with the main advantage from a linear strategy (fast-forward merge). This strategy is quite widely adopted and can be enabled with a single checkbox in the merge request settings for a repository:

This will result in merge requests that can only be merged if a fast-forward merge is possible, whilst still keeping the merge commit. This means that the commits from the feature branch are added on top of the latest commit on main with a merge commit so the entire merge can easily be reverted. It still means that the developer is forced to update their branch from main, but it gives them a clear indiciation that their branch is not up to date with main plus a button in the merge request to update the branch from main. This reduces the risk of human error and the overhead of updating the branch manually. You will only need to rebase locally when there are merge conflicts that need to be resolved locally.

Let’s look at a history where we update our feature branches from main using git rebase instead of git merge, but still merge feature branches into main with a git merge (resulting in a merge commit). This gives us a much cleaner history where the commits from the feature branch are added on top of the latest commit on main with a merge commit so the entire merge can easily be reverted.

Pro’s

- As you can see in the image below, commits still retain their actual commit dates; however, they are ordered based on when they were merged to

main. This leads to a much cleaner git history whilst still preserving merge commits allowing for easy reverts and traceability.

standard merge commits vs merge commit with semi-linear history

standard merge commits vs merge commit with semi-linear history

The main thinking here is that for our git history, we are more interested in when the commit made it to main than when it was committed on a feature branch, yet we still can easily see when it was actually committed because the date will remain the original date of the commit.

-

A merge requestt is not mergeable unless it is based on the latest version of the target branch. This means that any CI that runs on the merge request is guaranteed to provide the same results on the feature branch as on the

mainbranch. This is actually enforced by Gitlab rather than it being the developers responsibility to constantly keep their merge request up to date. (Especially valuable if review takes long and other MR’s are accepted in the mean time). -

Less manual fetching/merging/rebasing for the developer on their local machine, as they can update their branch from main with a single button click in the merge request.

-

No more superfluous merge commits, as seen in the image above, there are two merge commits less.

-

Branches can still be visualised in history editors like git kraken, but remain a lot more simple.

Con’s

Okay okay, it isn’t all sunshine and rainbows. There are a few downsides to this strategy as well, but I believe they are outweighed by the benefits and can be mitigated with some good habbits on the developers side.

-

When rebasing a feature branch, merge commits need to be resolved per commit. This means that if you have a branch where you change the same line multiple times spread over different commits and you rebase your branch (which conflicts with a new commit on develop) then you will essentially get a merge conflict for each commit and need to resolve them one by one in order of commits. This can be a little annoying but tends to not happen often.

This can be mitigated quite easily by making sure commits are not too small and squashing commits that affect the same line of code.

For example:

Commit A: Add “HelloWorld” function.

Commit B: Fix “HelloWorld” function because I forgot a return.

Commit B should be should be squashed into commit A, as it is essentially the same change. #hideyourmistakes

-

Semi-linear merging works very well when you have multiple developers working from develop but on their own feature branch using merge requests, but can become messy when multiple developers work on the same feature branch. This is because when you rebase your branch it needs to be force pushed and this can cause diverging branches. To pull after a rebase by developer one, the second developer can simply do git pull –rebase but this becomes harder if they have also just rebased in the same way. There are two possible mitigations for this:

A) Making sure one person (usually the branch owner or feature driver) is responsible for rebasing and communicating this clearly to anyone else committing directly to the same branch.

B) Not having two people commit to the same branch directly but instead use merge requests to feature branches as well. This is might be preferred when both developers are very frequently commiting to the same branch as it leads to less git branch nightmares and gitlab handles the rebase for you and let’s you know when your merge requests needs to be rebased.

-

I think one other thing to consider is that rebasing is a little harder than normal merging and onboarding junior developers or people with less experience with the various git flows might be more difficult. With proper documentation and instruction I don’t think this would be a significant enough risk to not use this strategy. I think you will find that if you teach them this early on, and show them how they can keep their branches cleaner and more up to date, they will be more likely to adopt this strategy and work well with it.

Conclusion

Git histories can become messy when working with multiple developers on the same project. By using GitLab’s semi-linear history, we can keep a much cleaner git history whilst still preserving merge commits for easy reverts and traceability. Combining this with some good practices around keeping clean branches and squashing commits that affect the same line of code, we can keep our git history clean and easy to manage. Frequently updating our feature branches from main and using merge requests to feature branches can help mitigate some of the downsides of this strategy.

Some helpful resources:

Git history and various merge strategies can sometimes be hard to understand and are most easily explained with visualisations (especially animated ones). Below are a few videos that do exactly this. Just keep in mind we will only rebase our feature branch and not the main branch (semi-linear vs full-linear)

-

By far the best explanation as it draws the git hstory with animations as he types git commands in his terminal Learn Git Rebase in 6 minutes // explained with live animations!